by Jonathan Baxter

I wrote this ‘response’ in December 2022 when SCCAN asked me about a deadline I’d committed to. I wrote it off-the-cuff. It’s my way of introducing an embedded artist residency I’m engaged in at St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh. The residency supports the Cathedral’s transition to net zero carbon by 2030 – albeit the language of net zero carbon and the likelihood of achieving it begs the question: is the climate and ecological crisis a technological crisis or something else?

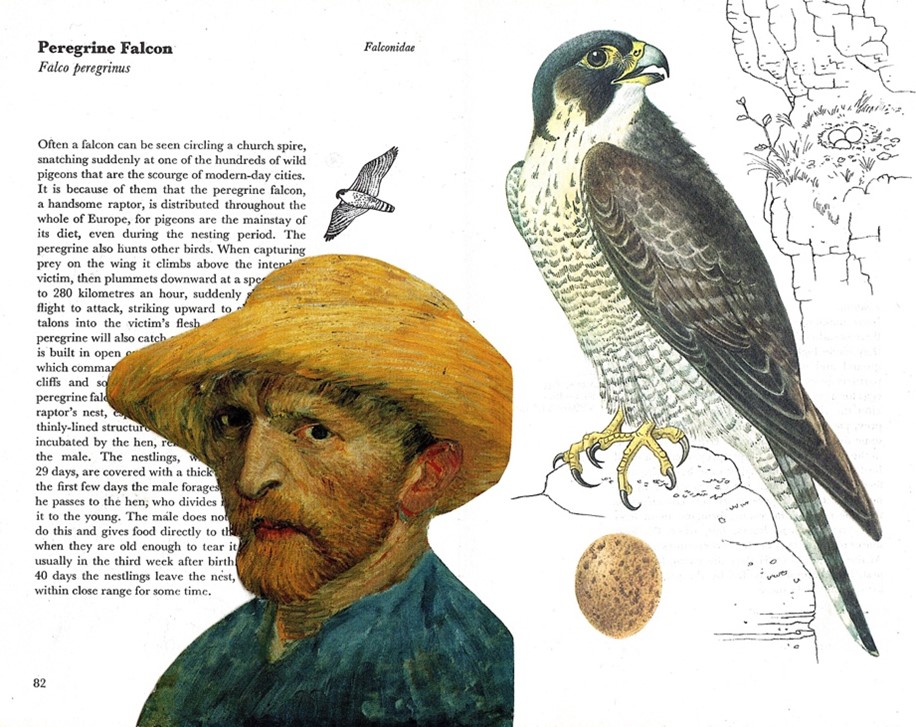

Don’t tell anyone but I’m undercover. An artist in residence at St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh. A peregrine hidden in plain sight. You just have to look up.

This is the deal: there’s a climate and ecological crisis. There’s more going on, of course: all manner of injustices. There are good things too: how the beech hedge changes colour from green, through yellow to copper brown. It’s waving at me now; leaves lifting in the wind. But there’s also the drowning. Waving and drowning. That’s the journey I’m on.

So, anyway, I’m undercover. Not always a peregrine. But that’s how it started. I attended a Cathedral eco-group meeting. They were talking about heating. How to heat the building. Then they spoke about pigeons. I wasn’t sure I should stay but then Mike said, “We need more predators.” My ears picked up. I swooped down. “I can be a predator. A good one; for the climate crisis.” (I can also be a pigeon.)

So that’s how it started. I took up my residency. Then COVID came and closed things down. Give and take. More or less. So, we met in the grounds of the Cathedral. And then we – a group of us – started walking. That’s also where it started. Before the peregrine. In the Song School with Phoebe Anna Traquair. Could I pick up my bed and walk? Could I pick up Traquair’s Song of Creation mural and walk it to Glasgow?

And we did. A Pilgrimage for COP26. Motley but good. Concerned about the climate and ecological crisis. Aware that COP26 was probably the last chance to turn things around; to keep the global net temperature rise at 1.5 degrees Celsius (max) above preindustrial levels. That didn’t happen. But then most of us – the pilgrims, that is – didn’t think it would. We were asking the wrong question. Or rather, we were asking the wrong people. A people, more or less, without conscious skin in the game.

To say it crudely:

‘“I am going to accept the situation, Judge Henderson,” answered John, with brevity that did not escape the keen old man.’ (W. E. B. Du Bois)

And after the walk, this: speed writing between emails and childcare. The occasional drawing. Too busy to meet with friends. All in aid of what? A peregrine’s descent? A peregrine’s dissent?

But the work continues. Life continues. For example, today my son, who’s three and half years old, told me a story about glaciers. He said, “In the North Pole glaciers don’t melt because it keeps on snowing.” I listened to his story, wondering who or what he’d been listening to. And I thought, what can’t I tell you? What information am I withholding? Is it true that glaciers in the North Pole don’t melt?

Now everything is melting. Everything is aflame. There’s no stopping or starting. It’s just a question of time and place. (Armour dissolves.)

Endnote

There are three things I’d like to say about this ‘story’. The first relates to the free association of images: they’re here in the room, outside my window, in my conscious and unconscious mind. (That’s the nature of my residency: it’s wholly contingent.)

The second point concerns the reference to Phoebe Anna Traquair’s Song of Creation mural. The mural was painted between 1888-1892 and depicts angels leading a procession of people and creatures illustrating the canticle Benedicite Omnia Opera (‘O all Ye Works of the Lord, Bless Ye the Lord’). As an artist in residence I take my lead from this mural to reimagine what a contemporary Song of Creation might look like, sound like, taste like, smell like, and feel like. For me, that means an ecological song.

The third point flags up two references: The first is an association to J. A. Barker’s book, The Peregrine (1967). When Barker wrote his book, the extinction of UK peregrines was predicted. Today it’s not. Credit for their recovery is due to the peregrines’ urban adaptation and limits to chemical agriculture. The second reference is to the Du Bois quote. It’s taken from his story, ‘The Coming of John’, found in The Souls of Black Folk (1903). It’s included, here, because it surfaced and because black lives matter; always but particularly in this context. It marks a transition in the story and stands for the unsaid; including the losses of COP26. Both texts are recommended, especially when read together.

For more information about Jonathan’s residency, see www.artandecology.earth

Storytellers Collective

Jonathan Baxter is an artist, curator and peer educator. His work explores, and supports others to engage with, the climate and ecological crisis, through a range of activities including reading groups, walks, performance events, festivals, tree planting, community gardening, curated exhibitions, and direct activism.