A reflection on energy, land, and life. While fictional in form, this story is based on a conversation between SCCAN story weaver Joana and former miner and rescue officer Sinclair in May 2024 at the National Mining Museum Scotland, in the village of Newtongrange.

A special thanks to the National Mining Museum Scotland, to Vicky, Megan and Sinclair.

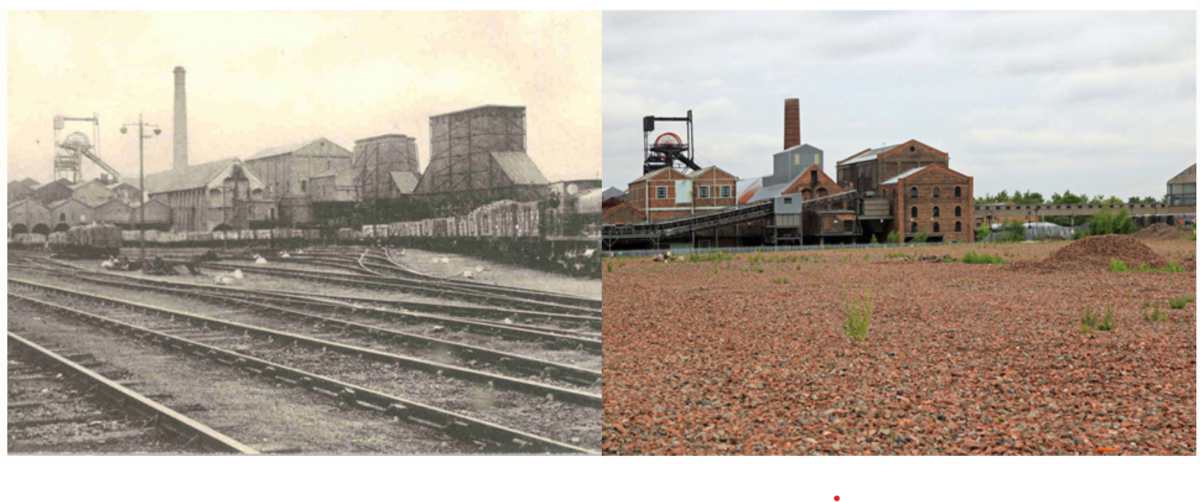

Cover Photographs: (1) 1980 Unknown © MIDLOTHIAN COUNCIL LIBRARY SERVICE (2), 2010 James Freeland © JAMES FREELAND

My son Lennox stretched his little toes out of the pram into the streak of sunlight pouring from the bus window. It was warm for May but the green Midlothian fields passing by were soothing. This green is one of the main reasons I moved to Scotland. It feels like renewal. It feels safe.

‘Almost there,’ I whispered, stroking his foot. We were on our way to Newtongrange, a former mining village I came to know after collaborating with National Mining Museum Scotland for an exhibition during COP26. It was about the impacts of climate change around the world and Scotland’s responses to it. It was a surprising collaboration for me, but one that I grew very fond of and now I wondered why I was so drawn to coming back, to this story or what might come of it.

Two years ago, my dear friend Ann Guedes passed away. I met her already in her mid-80s, at the end of her filmmaking career and the start of my writing career. It was a short yet profound friendship where I fell in love with her stories, and together we pulled and tried to stitch into some form all these amazing threads from her fading memory as she battled dementia.

Wishing to learn from stories of community action, struggle and truth, I enjoyed Ann’s campaigning films that highlighted the interconnection of workers and their communities, especially The Miners’ Film (1975) and UCS1 (1971). But my favourite became So That You Can Live (1982), an account of five years in the life of a female Welsh union organiser and her family, the struggles of striking for equal pay and the history of socialism in Wales and the mines. I thought of this film, and what I have learned at the National Mining Museum, and I looked outside at the greenery flashing by through the bus window. I could see all these shots of people looking at the landscape and remembering changes or wondering what has led to it looking the way it does.

I hopped off the bus pushing the pram towards the old Lady Victoria Colliery. Across the street at the museum offices, Sinclair was waiting for us. A former miner and rescue officer, now in his 80s and volunteering at the museum, he agreed to this conversation even though I couldn’t quite explain what it was about. The idea was for this to be a story about energy transition, to explore the parallels between the move from coal to oil and oil to renewables in a context of impact on communities, but I couldn’t articulate it very well because I am not sure that is entirely true. I am mostly curious about what Sinclair will tell me. I suspect he finds me slightly mad, but he is curious about me too. He welcomed us looking sharp in his suit and gave a warm smile to little Lennox who cooed in response. His blue eyes and Scottish accent feel strangely homely.

For the purpose of telling this story, it’s important to say it has been a while since me and Sinclair had this conversation and that I’m writing this during the worst most delirious flu of my life. I wake up at night drenched in sweat and when I can’t go to sleep, I think, and I think about this story and make notes.

Sinclair guided us to an office room, and we sat, each one at one side of the desk, Lennox on the floor with a snack. I opened my notebook and put my phone on the table, recording. I am not a journalist, and I was nervous.

‘So, Sinclair, what were the biggest changes to the community after the mines closed?’ I asked.

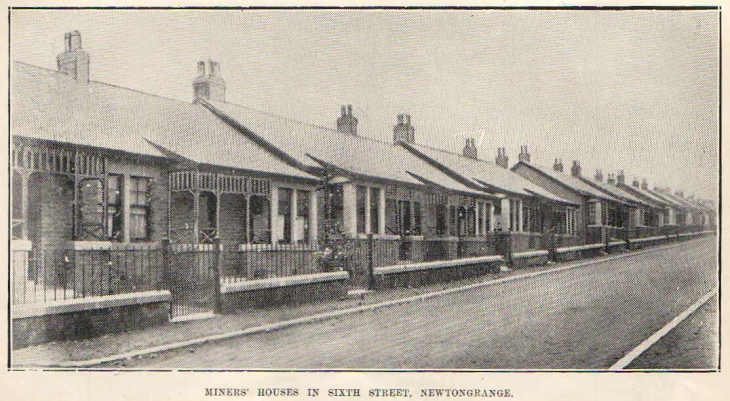

‘Well, the community had always relied heavily on the mining industry. Before nationalization and World War II, the job was there. It was a good job because it guaranteed income for hundreds and hundreds. But after the mines shut down in 1981, things changed a lot. Many of the men who worked in the mines had to start commuting long distances. The men who owned the coal owned the land and the houses, sold off properties in the area, and new land was developed into housing. The town eventually adapted, and now people commute to Edinburgh. At my age, I don’t mind the changes too much; they don’t bother me as much because I’ve seen how things evolve.’ He paused and took a long look at me with his kind blue eyes. ‘But you and your son have many more decades ahead here. It’s normal to worry about change.’

‘I feel like all I’ve known is change. Rapid change. All the time. It makes me dizzy, to constantly adapt.’ I saw him smiling and I shook my head, eyes moving from my lap to Lennox who had his arms extended for more snacks. ‘Sorry, I’m going off-topic. Thank you. And hm…’ I put my palm on top of my notebook, trying to portray a serious interviewer while the other hand gave Lennox a rice cracker. ‘What do you think are the biggest challenges facing the community now?’

‘Cost of living is a big issue.’ Sinclair answered sharply. ‘You see it in the people who visit the museum—they’re careful with their money because the local economy isn’t thriving. Jobs are different now, and there’s a lot of economic manipulation. More people are competing for fewer jobs. But this is a great wee village, proud of its heritage. It has music, it has sports. And it doesn’t have the same issues as inner cities.’ He shrugged. ‘But I didn’t stay here, I moved after my time in the colliery. I was a rescue officer in the mines in Ayrshire, and after the strikes in the 80s, all the mines closed, and I moved to my wife’s town. Our sons were born here in the village, though they went to school in the Borders. I joke about going back to Gorebridge and Newtongrange, but my wife says no.’ He chuckled softly.

‘Thank you, Sinclair. Well, this is the last question from my list,’ I felt my formal tone breaking up. Only three questions, this was awful preparation! I was sure I had more…I had to find them. But as I leafed through my notebooks, my mouth went on speaking, ‘What are your thoughts on the transition journey to renewable energy? There is an ethical and moral aspect to this energy transition, not just an economic one. We know it’s something we must do so that future generations can live on this planet.’

‘You are very unfortunate with whom you chose!’ Sinclair chuckled and his eyes remained kind as ever.

‘I don’t get to have these conversations a lot, you know, outside of the bubble of people who think like me. I’m curious. You can be honest, I really have no agenda’ This was true.

‘Alright. So yes, there are climate issues, and I know that. I’ve lived my life dealing with problems, and I believe in supporting communities, though it might not always help them organize naturally. Some people need help with strategic thinking, but not everyone does. Sometimes, I wonder if our interventions just create more problems. The world goes through cycles, and change is gradual. I’m not afraid of it, but there is a wee thing I worry about. Those who prioritize making money over improving the climate. Does that make sense?’

Did that make sense? There’s a lot of us working for benefit and fairness and another lot working for control and money. But also, could it be that we are trying to solve a problem in a similar way to how we caused it? What is important to preserve, and where do we need to innovate? And where are the conflicts of interest? I toss and turn on the sofa, feeling too hot, too upset, too awake and too aware. I read and scrolled for hours, a balloon growing inside my mind ready to burst. What is this idea inside of it?

‘Looking back, we have more people who can read and access information, learn about history, and understand how we’ve contributed to problems. But some of our meddling, like supporting the vulnerable, has been positive. Rising living standards matter—wealth for me means health, safety from disasters, and strong connections with others. Climate action should improve lives, but if we cling to old ways, will it really make a difference?’ I asked Sinclair. His voice and Lennox’s cooing echoed in the distance.

Connection. Corrections. I know there was some deeper meaning I was hoping to find in this conversation like I was hoping to find in the stories of the miners who lived in the belly of the earth, who powered the innovation and the knowledge and the light under which poetry was written.

‘My dear, we are getting old! Flu does get worse, you know,’ The fever breaks. My friend Nitzan. She’s with me in the living room watching a toddler Lennox. I cocoon back on the sofa. I sleep.

Sinclair’s voice brought me back.

‘We spend billions on wars, so much human life, but who’s really at fault? We are. We fight for our land, but maybe if we didn’t have all these borders, things might be different. Land and energy owners often cause conflicts to protect their interests. At my age, I’ve become disillusioned. I used to be a young socialist, arguing about everything, but now I see things differently. I admire your dedication, but after decades of doing this work, will you still feel the same way?

‘Probably not.’ I didn’t want to lie. I must not be scared of thinking what would happen if I change when I get old and tired.

‘That’s a realistic view. Your primary motivation is your son, and as you get older, it’s natural for your perspective to shift. You talked about the rapid change, the adaptation. Darwin, for example, was seen as crazy in his time, but evolution and adaption are part of our purpose. We’ve done some crazy things with land, borders, and religions—causing wars and conflicts. How can things get better? I see things differently now. I don’t give up, but I’ve come to believe that many of the fights I once had were perhaps not worth it.’

‘I understand. It’s a struggle to maintain idealism in the face of so many challenges. But maybe by addressing the basic things we all agree on, even amid the chaos, we can make a difference.’

‘I hope you find a way to balance your ideals with the reality of what you can achieve.’ Sinclair smiled and I thought I could almost see the young socialist behind the white hair and his impeccable shirt. His eyes shine the same.

‘Thank you, Sinclair. I’ll keep trying.’

‘And that’s all anyone can do. Keep at it, Joana.’

‘But… Sinclair, how do we know when we should meddle or not?’ I looked at Lennox, struggling to stand against a chair. But we are already out of the office, out of the bus.

‘You have to trust yourself and not want to be perfect. Humanity will never be perfect. Do it for love?’ Sinclair’s voice is still inside my head. ‘Within the Inuit tribes, it is common for the elders to be asked to dish out some advice. Well, I’ve been asked.’

I shake my head and take a deep breath. It wasn’t Sinclair who said this to me. It was Margaret Atwood, at the Edinburgh Book Festival. I apologise. As I said at the beginning of the story, I am confused. It’s not just the flu. All this happened a while ago.

‘My dear, we are getting old! Flu does get worse, you know,’ My friend Nitzan. Her face is full of wrinkles. She wears a pin on her blouse. I can’t read Arabic or Hebrew but she told me it means ‘we lived together’. Fifty years. I advance through the room, starting to see many faces. One of them comes closer to me. A man smiling, little white hairs starting to appear on his eyebrows and under those, eyes that look just like my partners’ but darker like mine.

‘Parabéns mãe! Oitenta e cinco primaveras!*’ he hugs me.

That’s right, Lennox. We made it. We lived. We still have spring.

*Happy birthday, mother! Eighty-five springs!