In this blog post SCCAN Story Weaver Lesley Anne Rose shares reflections on a day long workshop Living Well Locally, using the Place Standard Tool with a cultural lens. The workshop sat beside ways to also use the Place Standard Tool with a climate lens and facilitated deep thinking from participants from the cultural sector, local authorities and funders on how to use this framework for community empowerment and cross sector working.

“Birth deals us a hand of cards, but as important as their value is the place we are dealt them in.”

Ghostwritten, David Mitchell

Dunfermline is Scotland’s smallest city. Its rich and royal history boasts a previous life as the capital of Scotland and its Abbey is the resting place of seven of Scotland’s former kings, including Robert the Bruce. Views from the city centre roll south towards the Firth of Forth, the rust of the Forth Rail Bridge, gleam of the new Forth Road bridge and Edinburgh, Scotland’s current capital beyond.

It’s a city with ample green space including the 76 acres of Pittencrieff Park gifted to Dunfermline by the industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. The park is home to Andrew Carnegie House where Living Well Locally was being hosted.

Living Well Locally was a day to explore how the Place Standard Tool a simple and adaptable framework around which to structure conversations and assessments around place, could be applied to discussions around the role of culture within 20 Minute Neighbourhoods. Organised by Creative Carbon Scotland, a national organisation connecting arts and sustainability, there was also an inevitable climate focus to the day and the version of the Place Standard Tool adapted to consider place through a climate lens.

Living Well Locally formed part of Creative Carbon Scotland’s Springboard initiative – a long term collaborative project tasked with bringing about transformational change in Scotland’s creative sector to help build a net-zero, climate-ready world. Springboard looks at the systemic challenges that bring culture and climate together and started with a programme of national assemblies which grew into 12 cohorts each tasked with a different aspect of change for the cultural sector to work on, with the overall aim of continued collaborative working on systemic change. Cohort J, which I was part of, was dedicated to looking at how culture can contribute to the development of 20 Minute Neighbourhoods and the role that culture could play in them.

Initial meetings and discussions of Cohort J led to a focus on using the Place Standard Tool. This in turn led to a group made up of staff from local authorities, funders, cultural and climate organisations, architects and urban planners to gather on the top floor of Andrew Carnegie House to explore how cultural practitioners could act as trusted facilitators in statutory discussions about Living Well Locally.

Andrew Carnegie and his legacy is one of the many things that mark out Dunfermline as a place of note on the map of Scotland. Carnegie’s story of being born into a humble weaver’s cottage (now the Andrew Carnegie Birth Place Museum) to becoming one of the richest Americans in history, is well documented and has much to say about the importance of the places we are born into and the opportunities and infrastructure, or lack of, that influence us all from birth. As well as the need for many to move away from the places where we are born to find the conditions in which wealth and wellbeing can flourish in our lives.

Perhaps influenced by hardship in early years, Carnegie vowed to only pay himself a modest income from his vast, accumulated wealth and to spend his annual surplus instead on benevolent purposes. He devoted a large part of his later life providing capital investment for purposes of public interest and social and educational advancement. Funding the likes of libraries, education, museums, the arts and even Sesame Street – an American children’s TV series all about making your neighbourhood a good place to live.

The concept of 20 Minute Neighbourhoods puts a focus on living locally and, to quote the Scottish Government, creating ‘places where people can meet the majority of their daily needs within a reasonable distance of their home, by walking, wheeling or cycling’. The overall aim being to ‘help to deliver the healthy, sustainable and resilient places required to support a good quality of life and balance our environmental impact.’

Whether investment in improvement comes from the benevolence of individuals or the public purse, there’s no denying that place matters in all of our lives and that stark inequalities exist between them. The Place Standard Tool offers a simple and adaptable framework through which we can access place – generally or through a climate lens. Living Well Locally started with an explanation on the Place Standard Tool from Rebecca Dillon-Robinson a senior urban planner at Ramboll a global engineering, architecture and consultancy company.

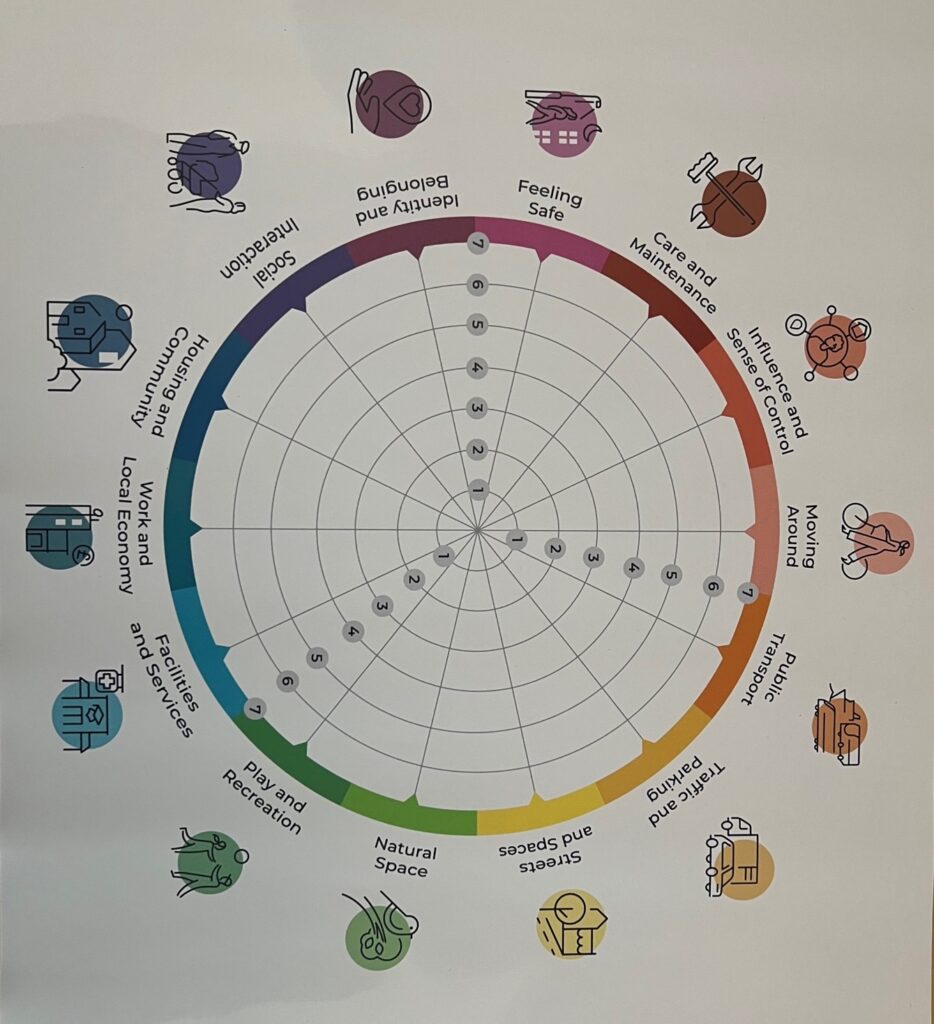

In essence the Place Standard Tool uses 14 categories based around the UN Sustainable Development Goals, as a starting point to open up conversations about the places where we live. Categories range from public transport to work and local economy as well as how much influence or sense of control people feel their communities have. For example, do residents feel safe or positively engaged? Do people feel they have stewardship and agency over the places where they live – key drivers of behavioural change. It’s important to factor in discussions around time and how a place can be different at different times. For example, a place can be considered safe in the daytime time, but not so at night.

Following conversations an agreement is reached to mark where on a circular chart the ‘Place’ scores on each category. The closer to centre of the circle a mark is placed, the less well the community scores in a category, the closer to the edge of the circle the better. By the end the process the dots are joined together to create a simple, visible picture of a place and how well it is performing.

The advantages of this process, and the map that emerges at the end of it, is that it’s an holistic approach that sits beside long reports and data, providing a visual statement on the strengths and failings of a community. If all of the categories are working together then a place is performing well, if not it’s easy to see what aspects of a place need improving.

Most importantly the Place Standard is a tool that enables and empowers communities to make these assessments themselves, helping them articulate what’s wrong, what they think it’s important to prioritise and how policy decisions impact their place. This can lead to bigger conversations around the possibility of initiatives such as community participatory budgets through which communities are given their own budgets and ability to vote on how it is spent. All of which invites a culture shift to take place within local authorities from one of looking at communities through a mind set of cutting and into one of collaboration.

This process can also be applied through a climate lens and the adapted climate Place Standard Tool focuses on two Big Challenges: ‘how can we achieve our target of net zero emissions by 2025?’ And ‘how can we adapt this place to already unavoidable climate change’. People can sometimes shut down when talking about climate, overwhelmed by the challenges ahead. However, the Place Standard with Climate Lens tool provides a framework through which difficult conversations around climate can be held and navigated. For example, by not talking about climate explicitly, but steering conversations towards access to local food and health and wellbeing.

“Teamwork is the ability to work together toward a common vision. The ability to direct individual accomplishments toward organizational objectives. It is the fuel that allows common people to attain uncommon results.”

Andrew Carnegie

Our first workshop of the day tasked us with having a go at using the climate change version of the Place Standard Tool, looking at questions around mitigation and transition and question the role of cultural organisations within this. All the time acknowledging the challenge of defining culture beyond buildings in a way that communities understand.

Discussions ranged from using cultural buildings as places of refuge to the role of culture in building trust and engagement within communities that are used to having things taken away from them resulting in a loss of enthusiasm and hope. As well as building ‘soft’ resilience by providing events and spaces through which neighbours can meet and get to know each other, rekindling old concepts of kinship.

“If you want to be happy, set a goal that commands your thoughts, liberates your energy, and inspires your hopes.”

Andrew Carnegie

After lunch Urban Designer and Chartered Landscape Architect, Jenny Elliott shared details of her creative placemaking projects through which she uses film, photography, visual arts and participation to catalyse change and collaboration, or reimagine overlooked urban places. For example, by using photographic competitions to help understand which places mean something to people and why.

All of which set the scene for the afternoon workshop through which we explored ways in which cultural organisations can work with local authorities to have place based conversations. Discussions considered the placing festivals and outdoor events not only within the culture departments of local authorities, but also community development and health and wellbeing. Undertaking projects that bring back a sense of pride to a place such as murals. The importance of archives and libraries in community development as spaces where people can connect with local stories and histories and the importance of this in place making. As well as communities having voice within cultural strategy. All of which requires cultural organisations to reconsider their place and relevance supported by more joined up thinking and cross sector working to open up access to funding and increase impact.

“As I grow older, I pay less attention to what men say. I just watch what they do.”

Andrew Carnegie

The day ended with a reminder that we don’t have time not to do action based things and we all came away with a list of actions and reflections to influence our work and planning.

- Create robust networks and partnerships.

- Develop the resources for culture to engage and raise its profile.

- Keep community at the heart of this work.

- Create a local place plan.

- Build peer networks and support spaces.

At end of the day we all came back together to draw together conclusions on everything discussed:

- As a society we understand growth, but not loss. In a time when things are shrinking the Place Standard Tool is a useful way to open up conversations and make tangible and visible the impacts of decisions on the places where we live.

- It’s important to define what success looks like at the start of a process of change.

- There are skills and knowledge within communities and a value in the exchange of both.

- Not everyone engages. Initiatives such as a steering group with trusted people within the community can be more effective.

- Include the Place Standard Tool in education and the curriculum and encourage knowledge about Community Councils and Community Development Trusts.

- The Place Standard Tool evolves and develops as it is delivered.

“It marks a big step in your development when you come to realize that other people can help you do a better job than you could do alone.”

Andrew Carnegie

We emerged from the day into the heavy autumn of Pittencrieff Park. When the Dunfermline Carnegie Trust, the organisation who had hosted us, invited proposals for the development of the park in 1903 they received an entry from the world-renowned urban planner Patrick Geddes. His proposal for Pittencrieff Park focused on the need to balance preserving heritage with regeneration. Although his proposal wasn’t successful, the thinking behind it remains relevant today. Whether you’re an urban planner, cultural practitioner or climate activist, there’s a need to preserve what’s good about a place within the drive for the regeneration required to make it better and resilient in a net zero future. More importantly, as the day taught us, there’s a bigger need for joined up thinking and working together to undertake the change required and the Place Standard Tool is an important resource to help achieve this.

Resources

What is a 20-minute neighbourhood? A useful blog by Sustrans.

UN Sustainable Development Goals

Scottish Government: Local living and 20 minute neighbourhoods